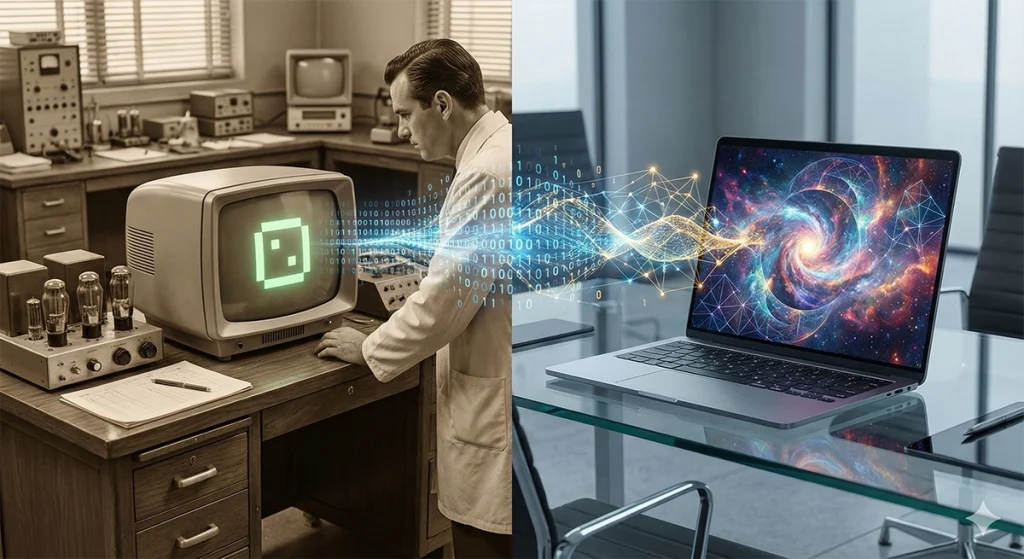

In the digital age, we take for granted that our smartphones recognize our faces to unlock, our cars detect pedestrians in the rain, and medical AI identifies tumors from a grain of a scan. These are the “eyes” of artificial intelligence. But the journey to achieve this—teaching a machine to interpret the visual world—has been one of the most grueling and fascinating chapters in computer science. What began as an optimistic summer project at MIT has evolved into a cornerstone of modern civilization.

Introduction: The Vision of the Machine

Computer Vision (CV) is the field of AI that enables computers and systems to derive meaningful information from digital images, videos, and other visual inputs. For decades, it was the “holy grail” of AI research. While a computer can calculate a million digits of Pi in a heartbeat, identifying a “cat” in a photograph remained an insurmountable hurdle for nearly half a century.

Today, CV powers everything from FaceID to autonomous vehicles. To understand how we arrived at this era of visual intelligence, we must look back at the audacious, and often humbling, milestones that defined the field.

The 1960s: The Audacious Beginning

The history of computer vision is often traced back to a specific document: the 1966 Summer Vision Project at MIT. Led by Seymour Papert, the project aimed to solve the “vision problem” by hiring a few undergraduate students for the summer.

The task was deceptively simple: connect a camera to a computer and have the computer describe what it saw. The researchers believed that by the end of August, they would have a system capable of segmenting objects from backgrounds and identifying basic shapes. This “historical optimism” proved to be a massive miscalculation. It turned out that “seeing” isn’t just about optics; it’s about the massive, complex processing the brain performs to make sense of light and shadow. The summer project ended, but the problem would persist for the next fifty years.

The 1970s & 80s: Understanding the Geometry

As researchers realized that vision was a deep problem, the 1970s and 80s shifted focus toward Geometry and the physics of light. The prevailing philosophy was that if we could mathematically model how light reflects off 3D surfaces and hits a 2D sensor, we could “reverse-engineer” the world.

A watershed moment occurred with the work of David Marr, a neuroscientist and psychologist at MIT. In his posthumously published book Vision (1982), Marr proposed Three Levels of Analysis:

- Computational Theory: What is the goal of the computation?

- Representation and Algorithm: How can this theory be implemented?

- Hardware Implementation: How is this physically realized (e.g., in neurons or silicon)?

Marr’s framework moved the field from raw pixel manipulation to a hierarchical understanding of “edges,” “textures,” and “2.5D sketches.” This era laid the mathematical groundwork for how computers could perceive depth and shape.

The 1990s & 2000s: The Era of Feature Engineering

By the 1990s, the field entered the era of Feature Engineering. Instead of trying to model the entire world, researchers focused on identifying “features”—unique markers in an image (like corners or specific textures) that a computer could track.

Two major milestones defined this era:

- The Viola-Jones Framework (2001): This was the first framework capable of real-time face detection. It used “Haar-like features” and was so efficient it allowed digital cameras of the early 2000s to draw those little green boxes around faces in the viewfinder.

- SIFT (Scale-Invariant Feature Transform): Developed by David Lowe, SIFT allowed computers to recognize objects even if they were rotated, resized, or seen from different angles.

While powerful, these methods were limited. They relied on “handcrafted” algorithms—rules written by humans to tell the computer what to look for. The machine still lacked the “intuition” to handle the messy, unpredictable nature of real-world images.

2012: The Deep Learning Big Bang

The true “point of no return” arrived in 2012 during the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC). As explored in the evolution of ImageNet, this was the moment data and hardware finally caught up to theory.

A team from the University of Toronto introduced AlexNet, a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). Unlike previous methods, AlexNet didn’t use human-written rules. Instead, it was “deep”—it had many layers of neural networks that learned directly from a Large-scale Dataset of 1.2 million images.

AlexNet’s victory was total. It reduced the error rate in image recognition by a staggering 10%, effectively proving that Deep Learning was the only way forward. This breakthrough shifted the entire AI community toward neural networks, leading to the rapid deployment of CV in smartphones, healthcare, and security.

The Present & Future: From Seeing to Creating

In the last five years, we have entered the “Transformer” era. Originally designed for text (like GPT), Vision Transformers (ViT) are now outperforming CNNs in many tasks by looking at images as a sequence of patches, much like words in a sentence.

Furthermore, we are moving from Discriminative AI (identifying what an image is) to Generative AI (creating new images). Models like Stable Diffusion and DALL-E represent the ultimate mastery of visual data—where the machine doesn’t just recognize a sunset; it understands the essence of a sunset well enough to paint one from scratch.

Conclusion: The Long Road to Visual Intelligence

The journey from the 1966 Summer Vision Project to today’s generative masterpieces is a testament to human persistence. It took decades to realize that vision is not a “simple” task to be solved in a summer, but a complex tapestry of data, geometry, and neural computation.

Today, computer vision is no longer a fringe academic curiosity; it is a fundamental layer of the human experience, providing us with digital eyes that never sleep and can see things the human eye can only dream of.

References

- Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition (LeNet-5)

- Source: Yann LeCun et al. (1998)

- URL: http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/publis/pdf/lecun-01a.pdf

- ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (AlexNet)

- Source: NeurIPS 2012

- URL: https://papers.nips.cc/paper/2012/hash/c399862d3b9d6b76c8436e924a68c45b-Abstract.html