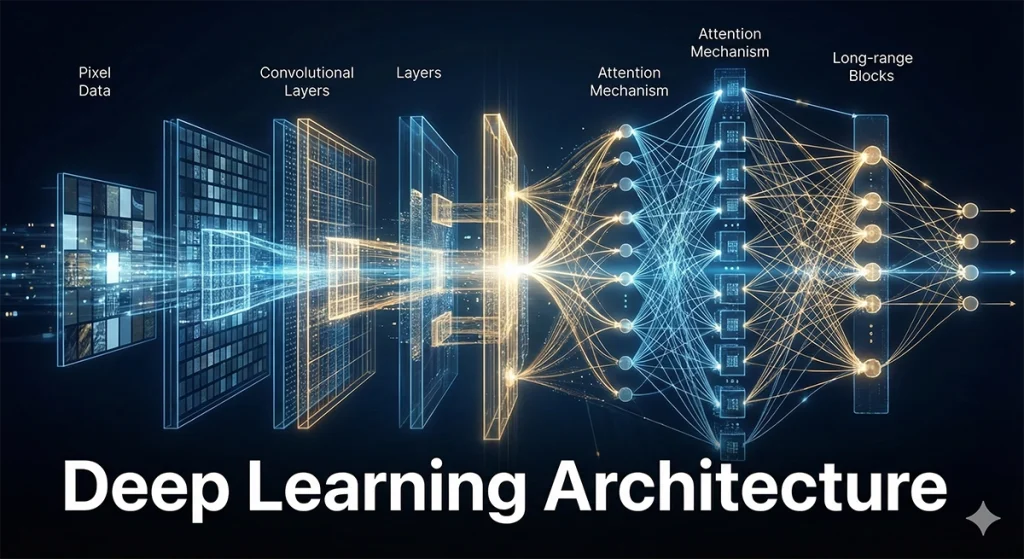

In the history of Artificial Intelligence, the transition from “programming” machines to “teaching” them is most vividly illustrated in the evolution of computer vision architectures. For decades, researchers painstakingly hand-crafted features—edges, corners, and textures—to help computers recognize objects. That era ended when Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) proved that the most efficient feature engineers aren’t humans, but the data itself.

Today, as we stand at the intersection of classical deep learning and the generative revolution, understanding the architectural backbone of how machines “see” is more critical than ever. This article explores the journey from the biological inspirations of CNNs to the transformative power of Vision Transformers (ViTs) and beyond.

The Biological Inspiration: Why Convolutions Matter

Before the deep learning explosion, traditional neural networks (Multi-Layer Perceptrons) struggled with images. The problem was spatial hierarchy. If you flatten a 2D image into a 1D vector, you lose the crucial relationship between neighboring pixels.

CNNs solved this by mimicking the human visual cortex. Inspired by the work of Hubel and Wiesel on the receptive fields of macaques, the Convolutional Layer was designed to preserve spatial structure.

- Local Connectivity: Each neuron connects only to a small region of the input.

- Weight Sharing: The same filter (kernel) is used across the entire image, allowing the network to detect a specific feature (like a horizontal edge) regardless of its location.

- Pooling: By downsampling the data, the network gains translation invariance, meaning it can recognize a cat whether it is in the top-left or bottom-right corner.

The Titans of CNN Architecture: A Brief History

The evolution of CNNs is marked by a quest for depth and efficiency. Each milestone below didn’t just win a competition; it solved a fundamental mathematical bottleneck.

1. LeNet-5 (1998): The Proof of Concept

Yann LeCun’s LeNet-5 was the first successful application of CNNs, used by banks to read handwritten digits on checks. It established the standard pattern: Conv → Pool → Conv → Pool → Fully Connected.

2. AlexNet (2012): The Big Bang of AI

Alex Krizhevsky and Geoffrey Hinton’s AlexNet was the catalyst for the current AI era. By leveraging GPUs for parallel processing and implementing the ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activation function, it decimated the competition at the ILSVRC 2012. It proved that deeper networks + more data + GPU power = superior intelligence.

3. VGG and GoogLeNet (2014): Depth vs. Width

The industry then split into two philosophies. VGGNet argued for simplicity and depth, using small 3×3 filters repeatedly. GoogLeNet (Inception) introduced the “Inception Module,” which applied multiple filter sizes in parallel, optimizing for computational “width” and efficiency.

4. ResNet (2015): The Breakthrough of Residual Learning

As networks got deeper, they suffered from the vanishing gradient problem, where signals became too weak to train the earlier layers. Kaiming He’s ResNet introduced skip connections (residual blocks), allowing gradients to bypass layers. This enabled the training of networks with hundreds or even thousands of layers, a standard practice today.

Beyond CNNs: The Rise of the Vision Transformer (ViT)

For nearly a decade, CNNs were the undisputed kings of vision. However, in 2020, a new contender emerged from the world of Natural Language Processing: the Transformer.

While CNNs are great at local patterns, they often struggle with global context—understanding how a pixel in the far left relates to one in the far right. Vision Transformers (ViTs) treat an image as a sequence of patches, much like words in a sentence.

- Self-Attention: ViTs use the attention mechanism to allow every part of the image to interact with every other part simultaneously.

- Scalability: When trained on massive datasets (like JFT-300M), ViTs consistently outperform CNNs, showing a “scaling law” that seems almost limitless.

The Future: Convergence and Foundation Models

The current frontier isn’t a battle between CNNs and Transformers, but a convergence. Modern architectures like ConvNeXt bring Transformer-like optimizations back to CNNs, while Swin Transformers introduce hierarchical structures back to Transformers.

We are now moving toward Multimodal Foundation Models (like CLIP or GPT-4o), where visual architectures are fused with language models. In this new paradigm, the architecture doesn’t just “classify” an image; it “understands” the scene in a way that allows for reasoning, generation, and interaction.

FAQ: Deep Learning Architectures

Q1: Why are CNNs still used if Transformers are more powerful? CNNs remain highly efficient for smaller datasets and mobile/edge devices. Their “inductive bias” (the assumption that local pixels are related) makes them faster to train when you don’t have billions of images.

Q2: What is the “Vanishing Gradient Problem”? During training, errors are propagated backward through the network to update weights. In very deep networks, these mathematical signals can become infinitely small (vanish) before reaching the first layers, making the network impossible to train. ResNet solved this with skip connections.

Q3: How does a Transformer “see” an image? It divides the image into a grid of squares (patches), flattens them into vectors, and adds a “positional encoding” so the model knows where each patch belongs. It then uses self-attention to weigh the importance of each patch relative to the others.

References

- Deep Learning (Review Article)

- Source: Nature (LeCun, Bengio, Hinton)

- URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14539

- Visualizing and Understanding Convolutional Networks

- Source: ECCV 2014

- URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/1311.2901